(Originally posted in Swedish on 3 November 2016.)

Over the past two days I participated in “Working Group: New Goals”, a meeting in Stockholm of the working group developing new goals ahead of the next ministerial meeting in the Bologna Process/EHEA, which will take place in Paris in 2018. The theme for the first day was Competencies and the theme for the second day was Digitalisation, when one of the speakers was Alastair Creelman from Linnaeus University, whose topic was “What is the role and impact of digitalisation on higher education? How can it be used to support teaching and learning at institutions, at the same time widening the access to higher education?”

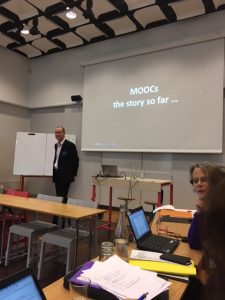

Part of the presentation was “MOOCs – the story so far”. MOOCs obviously come in various forms and have various purposes. Not all of them are massive, and not all of them are open. They may be intended as a teaser for an educational programme or as part of lifelong learning, and various hybrid models are being developed. Uppsala University is currently offering three MOOCs, the first of which, on antibiotic resistance, has just ended. But the second MOOC, Climate Change Leadership, starts on Monday – take the opportunity to try a MOOC if you haven’t done so yet, you can log in now. I can tell you, they’re rather addictive, right now I’m following a MOOC at Glasgow University on “The Right to Education: Breaking Down the Barriers.”

The meeting gave a feeling of déjà vu, particularly when State Secretary Karin Röding opened the meeting and welcomed us. I was most active in the Bologna Process 8 or 10 years ago, as a Bologna promoter, Bologna expert and national academic contact point (NACP) for quality assurance (QA). Karin Röding was a director at the Government Offices at the time and very active in these issues, perhaps most significantly through her work on the government bill “New world – new university”, which tackled three areas:

- Making higher education more international and more attractive.

- A clearer, internationally comparable degree system.

- Fairer, clearer and simpler admission rules.

It was in 2007 that Swedish higher education was given a three-level structure: first, second and third cycle. New degree descriptions were also introduced, specifying goals/expected learning outcomes, specialisation requirements defined in numbers of credits and qualitative requirements, and the exact number of credits required for degrees. I’m sure many of you remember how we had to define the level of all courses unambiguously in terms of goals/expected learning outcomes. All the syllabuses, everywhere in Sweden, were rewritten, masses of Master programmes were created and I talked about ‘Master mania’. The term ‘poäng’ (credit) was replaced by ‘högskolepoäng’ (higher education credit) and a standard academic year was defined as 60 higher education credits. I still feel grateful for the conversion table we were given that helped us to convert 1 credit to 1.5 higher education credits, 5 credits to 7.5 higher education credits – we’d never have managed without that table.

Perhaps I should write a few lines about the Bologna Process in general while I’m at it, it’s easy to take it for granted that everyone was there and remembers all about it. The Bologna Process is a European initiative launched by the Bologna Declaration, which was signed by 29 ministers in 1999. The overall goal was to make Europe more attractive, and to promote mobility and employability – a much debated concept. The operational goals were the adoption of a system of easily readable and comparable degrees, the introduction of a system consisting principally of three educational levels (cycles) and a system of credits, and the promotion of mobility, European cooperation in quality assurance and the European dimension in higher education. Other areas were gradually added, such as lifelong learning, the social dimension.

Today, 48 countries participate, ministerial meetings are held at longer intervals and the Bologna Process doesn’t have the intensity and tempo that it did ten years ago. Nonetheless, it’s a tool that we can use for working on higher education issues in Europe, we have a common arena and we have a language that enables us to pursue development together – and this mustn’t be underestimated.